EDI-ELG/STAGE 3/TORN-ELG

-ELECTROLYTES, +VOICEMAIL & SLURRY

TORNAGRAIN - ELGIN

Of all the things I discovered about myself over those past two days in the saddle, the one that kept returning was my body’s ability to keep going after depriving it of rest, adequate shelter or sufficient fuel. It would take a cursory internet search by Jen when she arrived in Elgin - ensuring that I had actually made it before her, so as not to ruin the surprise - to see that in my effort to stave off dehydration I had gone too far in the other direction, actually drinking too much water so that by the time the ride was over, I had over the past three days essentially flushed a fair whack of the energy-providing electrolytes from my system. That, combined with the lack of sleep and ability to fuel myself properly, had left my body fighting to keep ticking over whilst I subjected it to repeated efforts far beyond anything it had had ever coped with. The same issue of getting food/fluids in vs bringing it back up again would persist into Saturday, and meant that instead of the steak dinner Mum had lovingly made I would have half a baked potato and some beans at 8pm that night. By Sunday, however, my appetite would return, signalling some kind of caveman-borne regenerative process. Everything was delicious and staying down, and my weight was climbing back towards pre-ride numbers. It’s a testament to - and forgive me for straying into the kind of “we are all our own universes” self-help bollocks that’s making someone on Instagram very rich - the power of positive thinking. I’ll freely admit that at several points I got annoyed at myself or at the road, but not once did I think of stopping for good. The whole reason behind the ride, that to give something of myself to the road in order to see my folks at the end of it, pulled me onwards. And for the last few dozens of kilometres, I would have a companion to help pull me along in the shape of Steven.

Just like on the first morning with Neil, Perth seeming like a few millennia before, having someone riding alongside you has a magical restorative effect. Whilst no-one was going to win any KoMs that day, we shared the collective enjoyment of just riding along, and it bookended the whole experience for me quite neatly. Warmed by the sun once again easing its way through the subtle early chill, we made it to Kinloss in good time, S remarking that he had never seen the weather so fine nor the wind so non-existent on roads he was well used to training on. He was on his way to Findhorn to meet up with the rest of Team Gallagher, and so thanking him for his kindness - and for pushing me along a bit faster than I was probably capable of that point - I would ride solo for the final 12-and-a-bit miles into Elgin. I would take a total of three photographs.

By the time I reached Elgin I would have lost a stone and a half.

“If you were edible I would still be incapable of eating you.”

My speed dropped after we went our separate ways, something of the miles behind me finally sinking into the legs, but after one last sapping climb up around Alves I made it to the outskirts of Elgin. Tumbling down Brumley Brae, near the hospital where my mum worked, hitting the highest speed I would manage that day, I turned right and carried on past the bridge at the Cooper Park. Glancing across to Borough Briggs where my best pal David and I spent many an afternoon screaming mild obscenities at Elgin City FC, I could see the showies in full effect, thinking of past stories where the teen pregnancy rate would skyrocket every time the Codona family were in town, or when the guy I had bought my first proper skateboard deck - a Blind Gonz “Two Faces” board, for £8 - from threatened to kick my head in for writing my name on the Fairy Park miniramp. I headed left through the park, passing the magnificent old library where I used to rent cassette tapes of The Fall and once stole their only copy of Skateboard! magazine. The battle-scarred arches of the Cathedral loomed into sight, and I crossed the river at Pansport, now so close to home I couldn’t even tell I was pedalling.

Despite riding past countless fields turned yellow by the sun for most of the ride from Tornagrain to Elgin, it was about 1/4 mile from home - and nowhere near any fields - when the smell became noticeable. The end of the ride would mirror some of what had happened at the outset; little pockets of weirdness perforated the day’s activity of just riding along. It would involve three seemingly unconnected questions, all posed within a few hundred yards of each other: 1) “Have I had an accident?” 2) “Am I having an accident?” and 3) “Are those nuns?!”

The airborne toxic tang of slurry being sprayed on the fields is quite a familiar aroma to anyone who’s been anywhere near a farm, but the foul reek tickling my nostrils seemed different, and it had started doubling in its ferocity as I rounded the back of the industrial estate. Being so close to home I was on some kind of autopilot, but the slowly rising doubt in my mind that the source of the stink was in fact my own body caused me to stop and check that I hadn’t actually - and excuse my frankness here - inadvertently slurried my own paddock. Thankfully, there was no need to employ the spare bib shorts I had carried all this way, so I pushed on, the atmosphere so pungent it was almost chewable.

“ARE THOSE NUNS?!”

Along with the rear light, I had also lost the left-hand bar end plug on my handlebars somewhere along the line and it hadn’t really bothered me too much - I have in the past used an old wine bottle cork rammed into the handlebar end - besides having to look at the open end, the bar tape flapping about for however many miles. Then, there just at the side of the path my eyes are drawn towards a small black shape nestling in some grass. It is a bar end plug, a little scratched, but it will be an adequate replacement for the lost one so I slow to a halt, unclip my right foot and go to pick it up. More focused on my good fortune than the combined gravitational forces of bike + tired man, I find the ground is rushing up rather more quickly than I would like..

I can count on one hand the number of times I have failed to unclip properly on SPD pedals - and I remember each incident vividly, more for the embarrassment than for any pain each minor sideways tumble entails.

Whilst a pretty good return for the thousands of times I have successfully clipped in or out, the first failure to perform the latter is burned into my memory so clearly that I can remember every second of its slow motion awfulness. In the summer of 93 and I had taken my first proper roadbike - a Carrera Corsa with Reynolds 708 tubing and Shimano 105 bought at 50% off the RRP at the local Halfords, who were probably glad to be shot of this skinny tyred speed machine, since mountain bikes were all folk wanted to buy at the time - for its first proper ride with clipless pedals. I had bought some truly hideous Carnac shoes - tangerine orange, about 2 sizes too big - from the classifieds in Cycling Weekly and a set of gleaming Time pedals to complete the pro look. Inspired by le Tour and clad in Team Carrera kit - oh yes, the one that had faux-denim shorts - I was probably trying to just show off my new setup by taking a ride through town before hitting my regular riding route past Linkwood. At the time, Elgin High Street wasn’t pedestrianised, so there was a constant stream of traffic rolling along, passing either side of St Giles Kirk in the middle. As night descended, it would become a slow-moving procession of boy racers cruising endlessly up and down, some even reaching double figures in mph whilst they burned off £40 worth of petrol in their very own Fast and Furious prequel - Slow and Gormless you could say. But at midday on a Saturday it would mainly be teens hanging about smoking and shoppers out doing their messages, the perfect audience to show off my newly-developed pro skills on my turqouise-and-pearl speed machine. Coming along past St Giles and gliding to what was shaping up to be a textbook right foot unclipping at the lights, I notice some kids my age hanging out at the corner of Batchen Street. This momentary lapse in concentration is enough for my balance to shift underneath me, and instead of a perfect dismount I find myself toppling inexorably towards my left, my still-clipped-in left foot now performing a frantic, utterly graceless and ultimately unsuccessful wrenching motion as my arms leave the bars in preparation for hitting the deck. And hit the deck I do, my useless left foot folding underneath me and the bike slowly following it, the handlebars jamming into my inner thigh. The grannies outside the bakers look mildly concerned whilst the teens are properly losing it, pointing and roaring with laughter at the sight of this faux-denim Lycra-clad kid with massive orange shoes just lying in the middle of the street. I attempt to remount with as much coolness as I can muster but I can’t get my foot back in the pedal and slowly, shamefully wobble away as the cars beep behind me and the mocking cries of the teens recede. I have only a minor wee bruise on my hip but my pride has taken a Titanic-meets-iceberg dent and I vow never to ride my fancy road bike to school again in case of a repeat performance, potentially in front of the whole school. In an act of youthful stupidity I regret to this day, I will sell the bike to my flatmate Lambo for pennies whilst short of rent money a few years later; apparently it ended up following him to Canada so there’s little chance of a reunion any time soon.

“Join us on our leafy outdoor dining area, situated just 20 yards from the Landmark Centre.”

And so that familiar feeling of toppling towards the earth returns. Whilst there is nobody to witness it this time, it is nonetheless intensified by the fact that I won’t have a lightweight 14 speed road bike landing on me; rather, a fully-loaded steel all-terrain behemoth will be the inevitable payload. Some vestigial muscle memory kicks in, however, and I manage to pull my left foot out of the pedal and onto the ground before anything dramatic happens, but the bike still clatters onto the tarmac and I jar my hip a little. I get back on the bike, pocketing the bar end plug and thanking my spidey-senses for avoiding adding to the list of dishonourable dismounts.

A hundred or so yards further down the path my ears are pricked by the flatulent growls of two-stroke engines belting up and over jumps at the motocross track to my left. And then I see them; two women clad in pristine white robes, looking across to the bikes flying through the air. I whip my phone out and take a video as I am passing, and it is fleeting enough to make me question whether or not it is actually happening - two sisters of the cloth just checking out the bikers, chatting to themselves in what sound like North American accents. So, the slurry stink, the almost-crash and then the nuns, all within 180 seconds of each other. The road will provide, right to the end.

The same road from the year before, minus the stink, bar end and nuns.

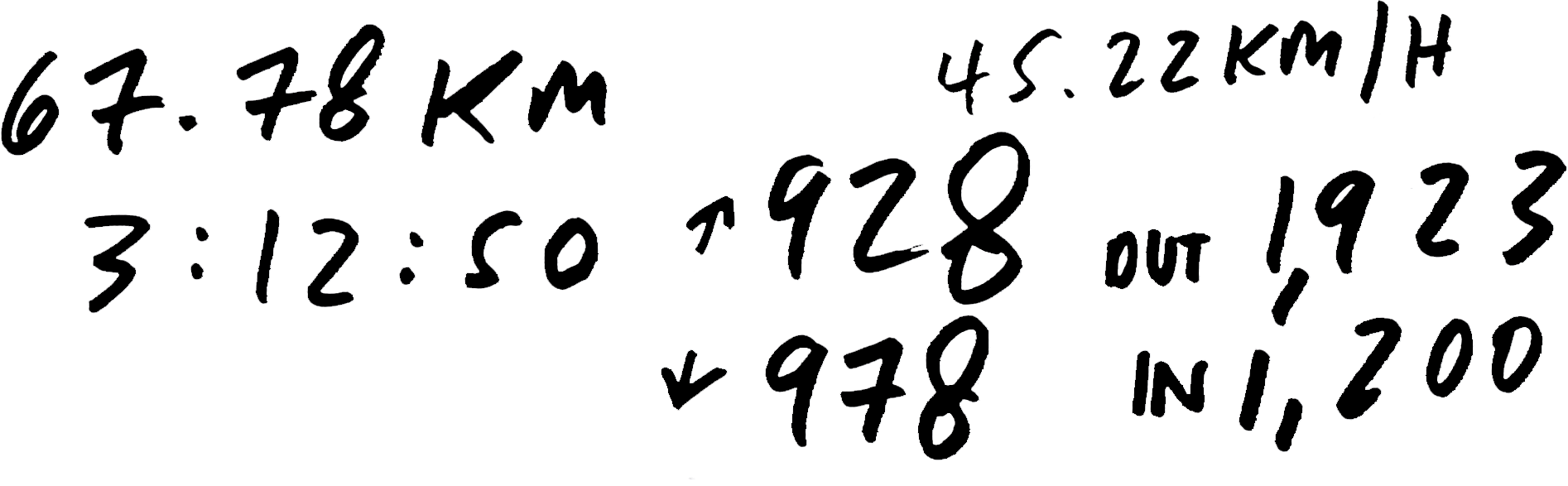

I had originally called this retelling of my cycle from Edinburgh to Elgin loss/gain since for the three days I had spent on the bike it seemed a neat summation of the balance required to do a long, multi-day bike ride. The graphic symbols I’ve used (up/down, stop/go, in/out, +/-) are a way of visually representing the raw statistics that going anywhere on two wheels involves; miles/kilometres travelled, feet ascended/descended, calories taken in/calories burnt. Somewhere in between all those numbers is just the act of riding itself, in that you can choose to focus on stats or you can just let them tick over in blissful ignorance. Riding a bike for pleasure is one of the finest things you can do - any number of inspirational quotes from H.G. Wells or moody copy from aspirational equipment manufacturers can help justify or quantify the effort you put into riding that bike - and at many points along the way did I find myself oscillating between a sense of achievement in how far I had travelled and the nagging doubt that I wouldn’t make it.

Going back over these words I fear I may have focused more on the challenges I faced rather than what, for me at least, would represent something of a subtle, perhaps only temporary, change for good in my psyche. I am a man more inclined towards tragedy than triumph sometimes, a legacy of my moody teenage self feeling constrained in a small town until I could find myself in cities, in travel and new experiences. I suppose it is far easier to talk about the physical efforts a long bike ride can entail, extracting a perverse sense of pleasure in the suffering and the miles and the uncontrollable peeing and so on. I think, rather, that in riding through and past all the incredible visual treats Scotland has to offer it can be as mountainous a task as a genuine hors categorie summit to do justice to it all, to condense to a neat soundbite what marvels we are lucky to live besides. Sure, you can appease the cycling gods by bashing out a few hundred words on the wondrous things that a body performing at its physical threshold is capable of, but it does a disservice to the roads you are riding if all you can see through the paincave is a small square of tarmac just in front of your front wheel; furthermore, it seeks to pigeonhole each emotional experience. Distance and physical exhaustion aside, it must be hell being part of a professional bike race sometimes; how much does a Grand Tour hopeful or a seasoned domestique really see of the landscape when they are screaming through mountain valleys on 25mm of rubber or destroying themselves up a cobbled climb somewhere in Belgium? Forgive me if I am incapable of adequately describing just how amazing our country is but I had in some way taken it all in, filing the cuttings from that day’s visual journal in some dimly-lit archive in my head. Slotting away the visions of ospreys at Boat of Garten, the caravan parked next to a house filled with hay near Calvine, the footprint I left on the freshly-laid tarmac path up towards Drumochter - the memories are coming in fast now, my fingers cannot keep up - how my tears along the way came flooding out not at the hardest points, but at those curious intersections beyond our control where emotions and an appreciation for nature’s splendour meet. Remember to look up.

It doesn’t need restating that the months that have passed since the pandemic began have been incalculably cruel for most of the world. Summoning the will to keep going, to see a chink of light/hope over the horizon has left most of us teetering between deep moments of sorrow/disbelief and tiny epiphanies of joy, the balance frequently tipping one way then the next. And as I neared the end, the waves of emotion that framed my achievement came surging through me.

354km in, I stopped at the end of the road to phone my folks. I had kept it a surprise for weeks, only issuing a few cryptic posts on social media and more out of cementing the need to fully commit to the exercise than to announce some kind of epic human endeavour.

So when I phoned Mum, the signal bouncing up to some high satellite then back down to the house 60 yards away, my hand was trembling somewhat.

And the call goes straight to voicemail.

What poetic justice to have come all this way only for the subterfuge to collapse right at the death. So, I get Dad on the phone. I had told them to be home around this time for “a package to be delivered, something for you to enjoy on the last weekend of Le Tour.” Dad says that Mum’s on the other line talking with her brother Tom; my Auntie Max had been in hospital and the diagnosis wasn’t great. I felt awful, and not only for Max, a stupendously glamorous and kind woman who was the perfect sidekick to my suave Uncle Tom and his curiously black hair, but that Mum would have to hang up just to receive some mystery package at the door. Two of the Taylors, neighbours who I grew up just three doors down the street from, appear in a car, incredulous that I had actually made it (we had seen them a few weeks before in Leith for a pint, and they were one of the few who knew about the ride). I feel bad I have to palm them off a wee bit as I am trying to complete the last dozen yards of the trip whilst telephony is failing me.

So I decide to just ride home.

The folks, Burghead, pre-Covid times.

If most of the miles of tarmac I had ridden up to that point had been unfamiliar, I could lay claim to knowing almost every square inch of the road leading up to my folks. We had settled there 30 years ago after moving all the way from Gloucester where I spent years 2-12, and then surviving a year in a freezing NHS house on Springfield Road, watching the little plot of land transform as the new house began to take shape. An entirely new cul de sac in an otherwise humdrum collection of identical houses, our little corner of New Elgin had assumed the moniker Little Canada owing to the streets being named after various Canadian provinces. In those early days before the mass house-building in New Elgin really shifted into high gear, you could walk out of our backdoor and enjoy an uninterrupted stroll across the mud to Pinefield. On occasions Dad would let me ride his Honda C90 up and down the same field in a kind of low speed homage to Escape to Victory. Manna from heaven for any skateboarder is freshly-laid tarmac, and as the new streets began to spring up around us, I spent many an afternoon on solo missions trying to emulate my four-wheeled chariot heroes. It carried echoes of the road up towards Drumochter, where I was literally the first person to ride up the freshly-resurfaced cycle path alongside the A9. I know this because I had to negotiate the churned-up verge past the levelling machine on foot, suffering some rather menacing stares from the beet-red roadworkers as my tyres made their first impressions on the still-steaming surface.

All those miles and memories of tarmac behind me, but the last ten yards would be the easiest.

Mum is in the front room with a phone to her ear, Dad opening the front door. I couldn’t tell you what my face was doing, but both Mum and Dad’s are wide-eyed with shock and disbelief. My helmet is off and the bike dumped on the driveway without my realising it, and the two greatest hugs of my life are closely behind. “Did you .. ? Did you cycle here?” Dad asks. I nod, blinking through the tears, my chest heaving against mum’s embrace, who is just repeating over and over, “I can’t believe it. I can’t believe it. I don’t want to let you go.”

Before they retired, my folks put in a combined 70+ years of service for the NHS. Whether helping keep people alive through community mental healthcare (Dad) or ensuring the elderly’s journey towards their final years/moments of life was dignified and gentle (Mum), those Thursdays where we clapped from our doorsteps/windows/balconies for people like them now seem like a distant memory. My folks dedicated their lives to the care of others, but the pandemic would see them face their own challenges, each day piling some new hurdle or horror onto the ever-swelling slagheap of anxieties. Mental and physical wellbeing became a battle of minds and bodies, and every time my phone rang it felt like picking up a live grenade. That none of us could be together, that no medical intervention was making enough of a difference to help navigate a path towards better health - or Christ, even normalcy - would be the hardest thing in the world. My folks are sociable people, and the pandemic would utterly obliterate that sense of belonging and sharing of love in a few short weeks. The Zoom calls started to resemble final transmissions from some distant or doomed interplanetary mission; we were all in our various ways slowly unravelling, grasping to keep the threads together whilst the numbers of dead tracked ever upwards and we feared for each other’s lives, not to mention our sanity. Working from home became second nature far too quickly, but it had its benefits. Aside from stripbars - and, I am told, a single branch of Farmfoods in Dumfries around Samhain - there are only a few work places that you can attend dressed in your underwear and not face disciplinary action. So much had changed that talking about “the new normal” was often as draining as having to adjust to it.

So when I decided to ride to Elgin it was with the understanding that I wasn’t really doing it for myself; I was doing for my folks, that my few hundred miles of alternate suffering and joy might repay in some way the sacrifices they had made not only for me, but for all the patients they had helped treat along the way. Each time I ignored my legs’ screaming rebellion, each time I forced down some food or felt the tears well up it was for them; my pocket-sized parents, who we could now spend a few days with as some kind of collective balm for the soul.

It would transpire that for all the good fortune I experienced over the few days on the bike - the dropped-then-recovered phone, the general good behaviour of my bowels, the virgin tarmac of the National Cycle Route, the outstanding weather conditions - none would top the fact that the weekend of the 19th of September was the final one two households were allowed to meet indoors. My seemingly-random choice of choosing to leave on the 17th meant that had I chosen to delay it by a week, by the time I reached Elgin I wouldn’t even be allowed inside the house.

Calton Hill, mid-Covid 19.

The memories from that golden weekend are somewhat scattered as my body slowly recovered. Dad and I watched the most remarkable penultimate day of Le Tour, where two Slovenians suffered the best/worst time trials of their careers. We ate, we all sat in the garden and reflected on recent and past glories over a dram or two.

Dad told me a story I had never heard before. When I was finally diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease it had been a warp-speed deterioration from mildly unwell to being rushed to hospital. I was 20 years old, and in the space of a few weeks had lost some 3 stone as part of my intestine had ulcerated then ruptured, leaking its contents into my body and causing me to be so sick. An operation to resection my punctured bowel was the only real clinical solution and I was - through the morphine fog - mildly aware that this was A Big Deal. Unbeknownst to me, Dad had cornered one of the consultants around the time of my procedure to ask about what would happen when the operation was over. Typically, patients who have had a bowel resection will require a stoma to reroute the bowel to the surface of the stomach away from the colon and rectum. The consultant was a bit blasé in responding to my dad, breezily saying “Well, he might need a stoma. I dunno,” to which my dad, possibly the most mild-mannered person I know, replied, “Listen, my son is twenty years old. He is going to wake up with all kinds of things sticking out of his body. You had better f-ing find out whether he is going to wake up with a stoma.” Sure enough, I did wake up with lots of things sticking out of - and into - my body but mercifully a stoma was not one of them, and I like to think Dad’s forceful enquiry had something to do with that. This didn’t quite dull the shock of having a tube inserted into my wee man, for I was unconscious at the time. This paled into insignificance during the removal of said catheter however, a traditionally delicate procedure performed for the first time and with more than one excrutiating attempt at bag deflation by a young male nurse who either went on to have a career as Scotland’s finest catheter removal officer or was dismissed within weeks for tearing another man’s urethra into ribbons. Either way, I recovered from the surgery and some 24 years on am more often symptom-light than fully crippled by Crohn’s, but it is a rather long game. The disease lurks on the fringes every day, that nebulous form drifting in the shadows, and I have an ugly grimace as a reminder carved into my belly, a 7” scar under my navel that is still numb in places and in one swipe of a surgeon’s scalpel ruined my career as a figurehead for the perfect six pack abdominals industry.

I write this as we enter another period of uncertainty, particularly here in the Central Belt of Scotland. What constitutes a booze-serving-café versus a pub-that-sells-cakes remains uncertain. Whilst Nicola Sturgeon et al seem to demonstrate empathy with the people they are asking to do hard things, the UK Government appears to be on mission to see how much they can get away with, some enormous punchline-free piss-take, a Jeremy Beadling of such epic proportions that when the cameras reveal themselves, the pranked are breathing their last in a suburban care home and the floor manager has flogged the TV rights to a vintage VHS operator. Despite this, many people continue to act as if nothing has changed. One of our slow-witted neighbours has had their kids and small grandkids visit several times a week since March and another - a stern, thick-necked, tiny-legged steroided sample jar of a human who we call Dorito Man due to his triangular shape - has been selling cars outside our flat, his customers seemingly as dense as him as they sit in whatever vehicle he is punting that week and hand over wedges of cash, all shaking hands at the end of the transaction. I have come close to wishing misfortune or even physical discomfort to visit them all, but am sure the Polis have bigger fish to fry/other skulls to crack. You could choose to let all this wash over you, to pretend that people are just doing whatever they can to get by, but it angers me to the point of screaming that a handful of idiots are unwilling to give up the tiniest concession to decent behaviour while people like my folks are driven further away from regaining some of their old ways of life. We have all had to change because of - and been changed by - the pandemic. Sometimes it feels that despite our efforts it has been in vain.

The reason.

But then, even some three or so weeks after the event and with life even more uncertain, I should try to retain that sense of positivity that fuelled large parts of EDI-ELG. Leaving my folks on the Monday was the hardest good-bye since the one some 18 years ago when they waved me off at Inverness Station as I left on the Caledonian Sleeper bound, eventually, for Japan and a year where I wouldn’t see them at all. I was young then, smarting from a break-up but facing a full 365 days in a new and exciting foreign land, my skateboard strapped to my rucksack. There would be many more trips up the A9 ahead of me. I would take enough decent images in Japan to convince me that my career ahead would be as a photographer, and I am mildly annoyed at myself that I didn’t stop to shoot more photos on my ride to Elgin.

But something else was driving me on, and it was the gift I could give to my folks. Before I left I hugged my mum once more, not wanting to let go. Through the tears I said to her, “Every time you feel down, or you feel like you can’t go on, just think of me, riding North on the road towards you.”

I’ll end with something I read recently by the writer John Banville. Many moons ago I did my MA in English Literature and Language and harboured aspirations of writing my own stories. Beyond an aborted attempt at a novel whilst unemployed or the occasional think piece or poem, writing is something that comes and goes throughout my life, the urge to put something into words not insistent enough to merit swapping one sporadically-paid creative pursuit for another. Perhaps it reveals itself at certain moments of significance, of life-changing events that happen during life-changing times. Banville writes,

“Any novel I am working on seems to have had no beginning, but to have been something always somehow under way; perhaps there is only one novel, of which every so often I publish a segment.”

I’d like to think that by collating these words about riding my bike for a few days in September I have committed a few chapters to the story of my own life.

Thank you for your patience reading these words, and in joining me for the ride.

Albie Clark

Edinburgh, October 2020

BEFORE / DURING / AFTER